Prime Target is a new series centered around a young mathematician working on the problem of prime numbers. Clearly, this is not the usual character or theme for a thriller series! However, the claim of the story is that the mathematician’s work on finding patterns in the prime numbers has the potential to disrupt all of the cryptography in use around the world and, of course, the bad guys are trying to stop him.

Needless to say, the show is swimming in mathematical references and images. Some are part of the storyline, and some seem to be just Easter Eggs for those in the know. I will try to catch and describe as many as I can, along with a little mathematical background when possible. I’ll do this episode-by-episode, and I won’t reference content of later episodes so there will be no fear of spoilers!

The Intro sequence

There are so many math images in the introduction to the show that it would take three days to enumerate them, let alone explain them. There are two ideas, though, that are worth pointing out up-front:

Many images show blocks or cubes in patterns or moving around. Prime numbers are defined only among positive whole numbers: 7, 53, and 2339 are prime, 8, 15, and 100 are not. On the other hand, fractional numbers like 5.6 and pi (31415926) are not even considered. This is why you don’t see much of the math you learned in high school: there are no parabolas, sine curves or even much geometry. The study of prime numbers is a subfield of “number theory” – the theory of whole numbers

.

One striking image that recurs in the Intro is a spiral composed of intermittent dots and spaces. This is an example of the “prime spiral”. The numbers, out to infinity, are illustrated as points along a growing spiral, with dots for those that are prime, and spaces for those that are not. The whole purpose of the prime spiral, created by mathematician Stanislaw Ulam in 1963, was to try to compress the infinite stream of numbers down to a small space so that he could more easily look for patterns*. The human mind seems designed to try to detect patterns, and the spiral seeks to take advantage of this

.

Episode 1: “A New Pattern”

Baghdad Market toys and ATM: The show opens with a noisy street market in Baghdad with scenes of buyers and sellers, including several shots of children. Two toys are shown being played with or bought. One is a very large bubble wand designed to create very large bubbles. It may be coincidence, but there’s a long history of using soap bubbles to explore concepts in mathematics. (I use them at least annually in my own math teaching in the study of optimization.)

The second toy may be more meaningful. A young boy is shown purchasing and playing with a colorful plastic Slinky. Slinkys are helix-shaped – sort of a vertical spiral -- and have an elegant mathematical description. (We have “Slinky Day” every year in my advanced Calculus class.) Of course, our own DNA is in the form of a double-helix – two helices, intertwined. It seems clear (to me, anyway!) that the Slinky is intended to reference the prime spiral.

Finally, just preceding an explosion, a woman uses an ATM to withdraw cash. ATMs must, of course, transmit information in code so that eavesdroppers cannot intercept it, modify the instructions, or steal password information. They are, in fact, one of the ways that ordinary people (not spies!) use encrypted communications on a daily basis.

Another spiral: There’s a striking close-up image of a vinyl record player at the start of Ed’s meeting with Prof. Osborne. Perhaps lost to the generation that grew up with streaming music, the sound from a vinyl record is created by small wiggles in plastic grooves on the disk. In fact, each side of a record contains one continuous groove arranged, you guessed it, in a spiral!

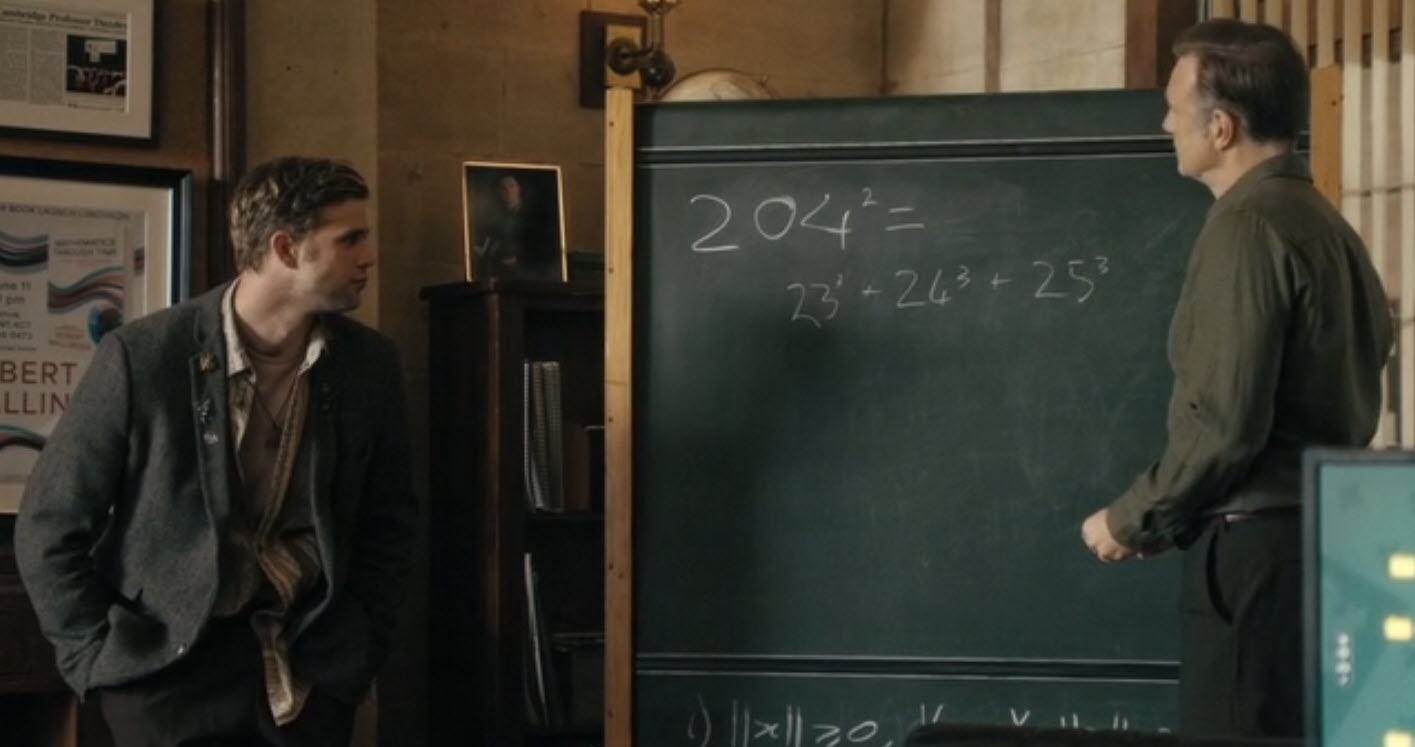

The number 204: Wow – Ed Brooks’ conversation with Prof. Ray Osborne is lifted right out of mathematics history! At their meeting, Ed quickly mentions to Prof. Osborne that his bus number was 204 and asks if this is an interesting number. Osborne quickly notes what Ed already knows – that 2043 is the sum of three consecutive cubes. This conversation is lifted out of a legendary conversation. G.H. Hardy, was a well-known mathematician of the 20th Century who largely worked out of Cambridge (the setting of Prime Target). Hardy went to visit brilliant Srivasa Ramanujan (ca. 1919) who was ill, and (so the story goes) mentions that the number of his taxicab was 1729, noting that it’s not a very interesting number. Ramanujan replies that it is, indeed, a very interesting number, being the smallest number that can be written as the sum of two cubes in two different ways. The story is sometimes recounted as evidence of Ramanujan’s brilliant command of numbers, but it turns out that this particular number fact came directly from Ramanujan’s research work. In any case, Prime Target has drawn this story almost whole from the Hardy-Ramanujan conversation. It is even the case that Ramanujan was ill, and we quickly learn that Osborne is ill as well! (See The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel, and the film based on the book.)

Also at that meeting there is something interesting/suspicious about the visual of Osborne upside down through a pair of lenses. This isn’t directly mathematical, but my suspicion is that inverted numbers or equations may play a role later in the series. Another inverted image appears when Ed plays with a glass crystal later in the episode.

The rooftop starlings: Ed brings a friend to the roof of a building and makes note of a flock of starlings. He reveals that he’s been trying to study their sequences of flight, looking for patterns. The flocking behaviour of birds has long been of interest to mathematicians. Each bird has access to only local information – the location of nearby birds – yet the flock forms, as a whole, interesting shapes and patterns that change over time. The study of the way in which local behavior of animals and of numbers leads to emergent results for the whole was supercharged by the development of computer models, in part because the mathematics is so complex. Stephen Wolfram’s A New Kind of Science (2002) strives to describe all science in terms of this phenomenon.

Ed’s homosexual encounter: There are, of course, many depictions of gay relationships in modern media, and happily so. One doesn’t need a reason to include this in a story line. However, I would be remiss to not observe the way this seems to rhyme with the story of the mathematician Alan Turing (1912-1954). Turing created a foundation for the field of computer science, but also was central to the Allies’ successful effort to break of German codes (cryptography) in World War II. Turing graduated from Cambridge in 1938. In 1952, Turing was prosecuted for homosexual acts, illegal under the law at the time. His homosexual activity was revealed when he reported a theft from his home by his lover, leading the authorities to investigate and discover his relationship. (See Alan Turing; The Enigma, by Andrew Hodges, and the film based on the book.)

Ed says “I’m not interested in applications, I’m interested in theory!” This also harkens back to G.H. Hardy, whose book “A Mathematician’s Apology” argues for the primacy of theory over applications. He writes “One rather curious conclusion emerges, that pure mathematics is on the whole distinctly more useful than applied.”

The concept of zero: This scene, discussing the origins of a symbol for zero, contains a most lovely phrase “A cipher for nothing”. Kudos to the writers for this! The word “cipher” has many connotations. It can simply mean a symbol representing something. Or refers to something inscrutable, as in “He’s a cipher – I can’t figure him out.”. Or as a reference to code itself. Among cryptographers, “ciphertext” is the name given to the coded version of the “plaintext” of a message.

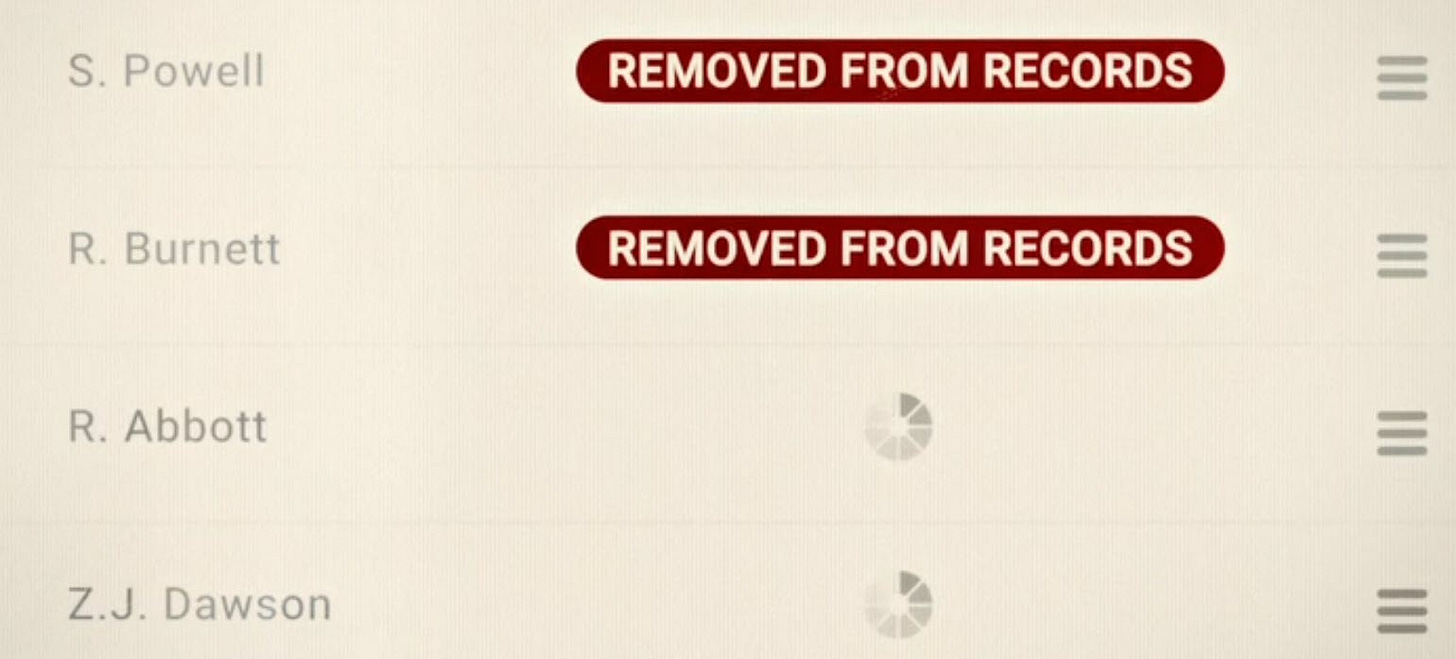

Research on Primes: In every film about a profession, be it teaching, or nursing, or police work, there are moments when anyone versed in the field rolls their eyes and yells at the screen. That moment in Prime Target comes when Ed discovers (gasp!) that all of the papers about prime numbers have been deleted from the library! Oh, my.

First, there is a ton of research into primes. Truly, thousands of papers from mathematicians across the centuries and around the world. To think that all prime research has been suppressed is like imagining that all newspaper articles about the 1969 World Series have been mysteriously deleted.

Second, research and papers are almost always shared upon completion. If these papers were of any significance, there would be copies in the hands of other mathematicians everywhere. Now we have to imagine that the articles about the 1969 World Series have been clipped out of the newspapers in every home that kept one!

What do prime numbers have to do with cryptography? A code, be it used by spies, ATMs, or online shops, is a process by which a message (a sequence of letters/digits) is converted to a new sequence to be transmitted. It is essential that the process cannot easily be reversed by a third party who sees the new sequence – that’s the point of the code. What we need, then, is a process that is easy to perform, but hard to undo. Omitting many details here, such a process is the multiplication of numbers.

It is easy, using grade school arithmetic and pencil and paper, to multiply 199 and 277 to get 52907. Consider the reverse process: given 52907, can you find the two numbers that were multiplied to obtain it? It is possible by just trying many numbers, but for very large values, hundreds of digits long, it becomes impossibly time consuming.

Finding these numbers is called “factoring”, and we all factored numbers in high school for various purposes, such as reducing fractions. We were able to do this because many numbers have small-sized factors which simplify the problem quickly. To factor, for example, 126, we see that it’s even so we can divide by 2 to get 63. We recognize 63 as divisible by 3, and thus get 21, which is 3 times 7. So the factors of 126 are 2, 3, 3, and 7.

Prime numbers are those numbers which cannot be factored. Their only factors are 1 and themselves. 199 is a prime number – no other whole number divides evenly into 199. If we take two very large prime numbers and multiply them, it become exceedingly difficult to factor the result without knowing the numbers. This is a one-way process that can be used to construct a coding system, and systems based upon this are at the root of nearly all of the cryptography in use today.

Ed is pursuing a pattern in the prime numbers. In principle, if there were a rapid way to generate prime numbers, our cryptographic systems would be vulnerable. Instead of guessing a massive number of possible factors, we could just try a smaller number of prime numbers generated by Ed’s algorithm.

Find Episode 2 mathematics here !

* “Remarkably, noted science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke described the prime spiral in his novel The City and the Stars (1956, Ch. 6, p. 54). Clarke wrote, "Jeserac sat motionless within a whirlpool of numbers. The first thousand primes.... Jeserac was no mathematician, though sometimes he liked to believe he was. All he could do was to search among the infinite array of primes for special relationships and rules which more talented men might incorporate in general laws. He could find how numbers behaved, but he could not explain why. It was his pleasure to hack his way through the arithmetical jungle, and sometimes he discovered wonders that more skillful explorers had missed. He set up the matrix of all possible integers, and started his computer stringing the primes across its surface as beads might be arranged at the intersections of a mesh." “ (https://mathworld.wolfram.com/PrimeSpiral.html)